Nigeria’s tiered electricity tariff system has once again become the center of intense public debate, as consumers, energy experts, and policymakers clash over its fairness, effectiveness, and long-term impact on the country’s fragile power sector. Introduced in 2020 by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission, the framework was designed to align electricity pricing with the number of hours of power supplied daily, but years later, it remains deeply controversial.

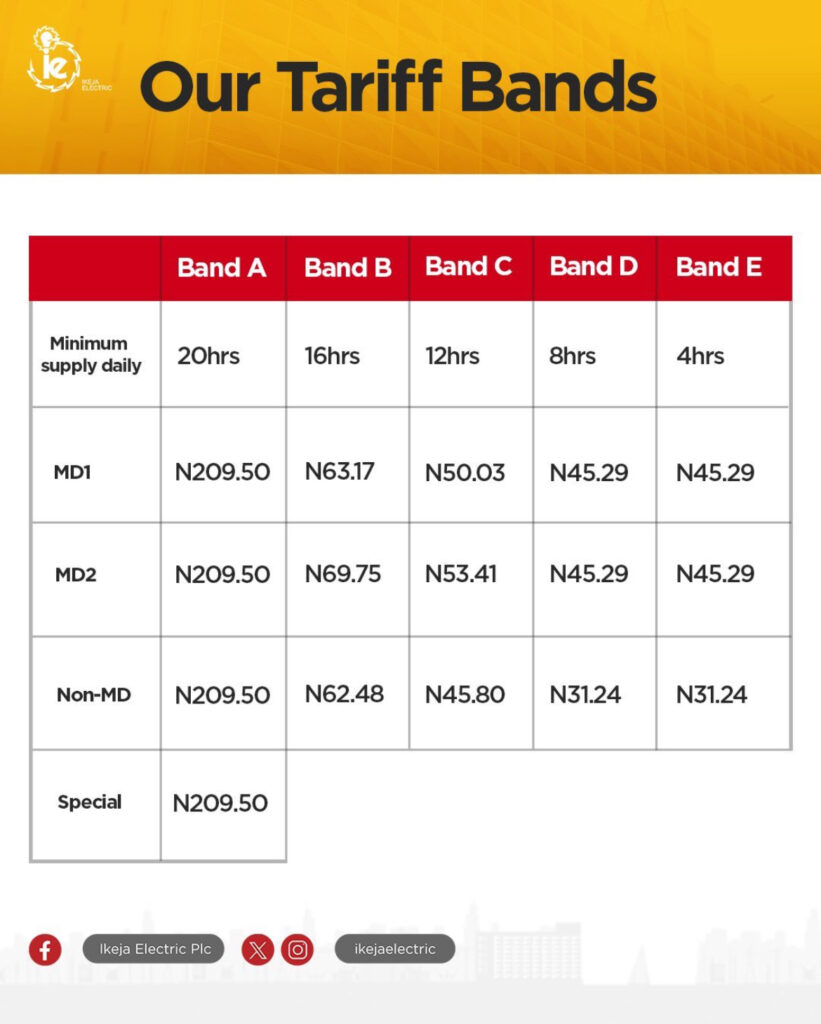

Under the system, electricity customers are grouped into Bands A to E. Band A consumers are expected to receive a minimum of 20 hours of electricity daily and currently pay about N209.50 per kilowatt hour. Lower bands receive fewer hours of supply, with Band E customers paying as low as N31.24 per kilowatt hour. The structure was created to encourage cost recovery for distribution companies while offering reduced tariffs to customers with limited access to power.

Defending the model, officials within the Nigeria National Grid and power sector regulators argue that electricity generation and distribution come at a high and largely fixed cost, regardless of how many hours power is delivered to end users. According to sector insiders, lower tariffs charged to Bands D and E do not reflect the actual cost of electricity production and are sustained only through heavy government subsidies. These subsidies, they say, have accumulated into significant debts that continue to weaken the financial health of the power sector.

Industry stakeholders warn that without improved liquidity, it will remain difficult to upgrade transmission infrastructure, reduce outages, or expand generation capacity. They insist that cost reflective tariffs, particularly for premium supply bands, are necessary to stabilize the grid and attract investment into Nigeria’s electricity market.

However, many Nigerians remain unconvinced. Public reaction across social media and consumer advocacy platforms has been overwhelmingly critical, with users describing the system as fundamentally unfair. Critics argue that the cost of generating electricity does not differ based on location or customer band, questioning why some consumers should bear significantly higher costs for a service that is often unreliable.

A recurring complaint is that even customers classified under Band A frequently experience prolonged outages, despite paying premium rates. Many report receiving far fewer supply hours than promised, raising concerns about accountability and monitoring within the classification system. For these consumers, the issue is not just pricing, but the gap between policy promises and real-life delivery.

Calls have also intensified for alternative solutions. Some Nigerians are demanding a nationwide rollout of prepaid meters to ensure transparent billing and eliminate estimated charges. Others argue that instead of subsidising electricity indirectly through tariff bands, the government should consider direct cash transfers to vulnerable households, allowing market pricing while protecting low-income consumers.

Energy analysts note that Nigeria’s power sector challenges go beyond tariffs alone. Ageing infrastructure, gas supply constraints, vandalism, and weak transmission capacity continue to undermine service delivery. While the tiered tariff system was introduced as a reform measure, its success depends heavily on consistent power supply, transparent regulation, and improved trust between consumers and service providers.

As discussions continue, the debate highlights a deeper tension within Nigeria’s electricity reform journey. Balancing affordability for citizens with financial sustainability for operators remains a delicate task. For now, the tiered tariff system stands as both a policy experiment and a flashpoint, reflecting broader struggles within the country’s quest for stable and reliable electricity.

Leave a Reply